Kristen Cussen and Kyshia Osei

Toronto is a globally recognized creative hub, but many Black actors and filmmakers still find their creative journey in this city includes battling barriers behind — and in front of — the camera.

So what does it take to succeed and change the system?

One shining example of someone working for change is celebrated Toronto-born actor Shamier Anderson.

He is considered a rising Hollywood star along with his brother Stephan James. His growing list of credits includes dear White People, Space’s “Wynonna Earp,” the crime feature, “Destroyer,” and the network series Goliath.

He noticed the lack of Black representation in the film industry in Toronto, and started the Building a Legacy in Acting Cinema + Knowledge (B.L.A.C.K) Ball.

The event is held every year, and its website says it is designed to connect “specifically diverse talent to the industry in an effort to cultivate mutually beneficial relationships.”

The B.L.A.C.K. Ball has been partnering with the Toronto International Film Festival for the past 12 years to help fund programs that serve young Black artists and promote homegrown talent.

But how else can local Black artists be helped? What work needs to be done?

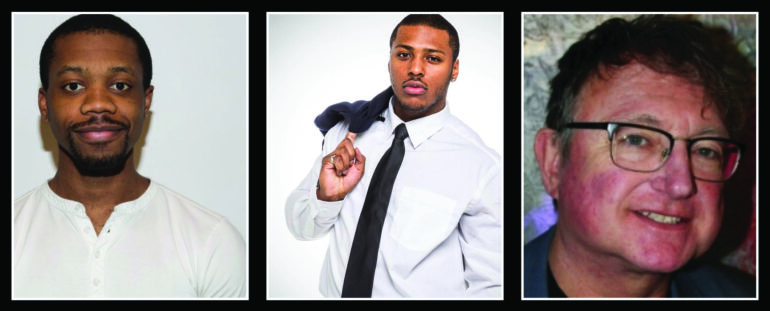

Humber News brought together three different perspectives — a Black filmmaker, a Black director, and a critic — to discuss their experience in Toronto’s entertainment industry.

3 perspectives on the industry

Jabbari Weekes is a filmmaker and co-creator of Next Stop, a series that blends comedy and commentary while following the lives of Black Torontonians while they face all-too-familiar challenges like rent, job hunting, and ‘making it’ in Toronto.

Akil McKenzie, is a self-made Black director, editor, and cinematographer in the GTA. McKenzie, a Sheridan film graduate realized that the reality of uncertain work was not something he wanted for his career. He created Falling Motion, a Toronto based video production company, as a way to freelance and start his career.

Jim Slotek has been a columnist at the Toronto Sun since 1983. His long career in Journalism led him to become a critic known for various reviews in the entertainment industry.

Here is a selection of their thoughts on various issues.

More than just a ‘Black creator’

In this part of our conversation, we looked at the need for Black artists to be recognized for their work and not their race.

Akil McKenzie: “I never want to get trapped in the idea of, I’m just that Black creator. I want to be a creator who’s Black. I don’t want to be a Black director that’s always put in the front because he made ‘the Black thing’, you know. I want to be able to just make frickin Sci-fi — just a nice little romance story happening in space.”

Jabbari Weekes: “In 2018, I had to be part of this really big Toronto rap documentary 6ix Rising, right… I felt like I was being used almost as a shield. Like, ‘we have an editor of music, who is Black, who’s overseeing this documentary, but really, he’s just kind of there to pretend like we’re doing progressive things.’”

Jim Slotek: “It’s similar in some ways to when we talk about trans actors, and LGBTQ+ in that, ‘do you want to be known as a person who plays this role only, right?’ It’s not just a matter that there should be more parts for people of colour, and there never have been. If there’s a role in the script and the race of the character is not mentioned or matters, the actors of colour should have an equal shot at that. But the presumption has always been if they don’t say what race they are in the script, they’re white.”

Breaking the mold

In this part of our conversation, we talked about the need to expand roles for Black artists

Akil McKenzie: “It’s a lack of education and experience. Your perceptions of people begin in your childhood when you see how people are depicted on TV. If you are from whatever background you’re from, the only version of Black that you know is what you’ve seen on TV.”

Jabbari Weekes: “You get the super over-earnest stories where every story is, ‘oh, am I going to be a gang member? Or am I gonna have a 250-60K job in an office?’ Life is never really that simple.”

“For us (Next Stop) we wanted to keep to the modern Toronto-scape. These are also our stories and stories of other people. And let’s have a real conversation about it instead of that extreme that I think a lot of dramas like to touch on in Canada and in North America in general.”

Jim Slotek: “In the 70s it was blaxploitation. You had Black movies like Coffee and Kareem and people weren’t taking it seriously. In the 80s, it was slavery and racism. What you’re seeing now finally, there are certain movies that still fit in the Roots era, like 12 Years a Slave, but then there’s stuff like what Jordan Peele is doing, which is an absolute — if you don’t mind my saying — mindfuck. You know, he’s making the movies he wants to make.

Black stories aren’t ‘niche’

In this part of our conversation we talked about how stories featuring Black artists can be made and marketed to all audiences.

Jabbari Weekes: “There’s still the studio thrust of ‘okay, how do we make this niche but still as broad as possible’ and that doesn’t necessarily work.”

“There is specificity and for us (Next Stop) specificity is authenticity. The core people we are depicting in this show are Black Torontonians, but we have a lot of big stories that can touch a lot of different people regardless of your background.

Akil McKenzie: “When we create something, I feel like there’s a lot of individuals who immediately decide, ‘okay, now I need to go show this to other Black guys, because they’re going to understand it, and they’re going to want to view that.’ When we showcase straight to that audience, that’s cool, because they all see it. But we kind of start limiting ourselves, and we stay in this bubble because we’re not necessarily trying to market to a larger demographic, just because we think they won’t like it.

Diversity as a ‘trend’

In this part of our conversation, we looked at the issue of colour-blind casting and not getting stuck in a specific box or category

Jabbari Weekes: “People want BIPOC creators, but even then there’s still the studio thrust of ‘Okay, how do we make this niche but still as broad as possible?’ and that doesn’t necessarily work.”

“We’re now in a space where it’s proven financially, bluntly, in terms of industry, that having diverse voices inhabit a mix of different interests in people and sexualities, and content can be super beneficial.

Jim Slotek: “It’s money. If there’s money in something, then that’s where they’ll go. And for the longest time, there couldn’t be a Black leading man, because you know, who would go see that? Until you had a Black youth leading man. Denzel Washington, Will Smith, and others. If the money comes in, that turns a lot of heads. And whether it really changes attitudes, sincerely, I don’t know.”

Akil McKenzie: “I want it to get to the point where there can be an Asian female lead. And it’s not wild that she’s Asian, or that she’s female, she’s just the lead, you know what I mean? It’s a tricky line to cross. On one hand, we need to be discussing the issues and everything going on, and consistently talking about what’s happening within culture and fighting for representation. But at the same time, we don’t want to push it to the point where we kind of like, alienate ourselves and become this box.”

Audience and second chances

In this next part of our conversation we looked at the changing ways Black filmmakers can reach audiences and thrive

Jim Slotek: “What’s always astonished me about movies that are directed to African Americans like Madea and stuff like that, is people go out in huge numbers. You can say whatever you want about them, but I think they’re an audience that proved they can vote with their wallets.”

“There are white filmmakers who have bomb after bomb and keep getting chances. Whereas I have heard Black filmmakers say, ‘I mess this up, I’m not going to get another chance’ to the extent that that’s part of the institution. That kind of has to change.”

Jabbari Weekes: “Next Stop does not exist without social media, I think without it we would’ve just kind of died.”

“Season one of Next Stop is completely self-funded. So there’s an ownership of the IP that we have, that would not have been the case had we developed the show with CBC. And again, it’s a rare situation, where we’ve established a tone of voice with our soul, very core, but growing audience. CBC, just on the financial side doesn’t want to dismiss that.

Looking up the ladder

As we wrapped up our conversation, we looked at the need for BIPOC leadership at the very top of the filmmaking world in order to create a chain reaction of real change

Akil McKenzie: “It’s not necessarily that you’re hesitant to work with an individual that’s Black or Brown. They’re just from somewhere else, and you haven’t been exposed to their work or gotten to see their work. You haven’t worked with people in that area.”

“The way to get more of us in there, to have more people of colour on set or in the film, is we kind of need to be there, you know, we need to be in a space where we’re seen. And if we’re not able to be in that space, we need to be able to encourage others to be looking over somewhere else.”

Jim Slotek: “There are so many factors that need to change. I mean, part of it is who hires. It’s producers, and it’s directors and casting people. So you’re looking all the way up the ladder, and what are you seeing? If even unconsciously, people tend to hire people like themselves, then you need to have diversity up at the top.”

“Once more diverse representation is in the actual engineering part of making a movie then the rest seems to follow.”

Akil McKenzie: “We’re here. We’re doing it. We’re fine.”