On the morning of Sept. 11, 1973, my father Pedro Riquelme was walking to his office when a passerby told him to back home. Quickly.

Confused, he would be told the Chilean military was moving into his town of Valparaiso.

More than 116 kilometres to the southeast, General Augusto Pinochet and the Chilean military began their siege of the capital Santiago. The rest of the country would soon follow.

A coup d’état and, later, a military junta in his home country more than 50 years ago is the reason my dad and my family call Canada home today.

“I could hear gunshots coming from everywhere,” he said. “Soldiers would take prisoners behind the building, and you would hear gunshots.”

The country was in chaos, he said. People were being gathered and loaded on boats and trucks, civilians beaten and shot in the streets, and homes were being broken into by military personnel, all for the sake of eliminating the socialist threat and suppressing the people.

“There were a lot of people who resisted but with the strength they had, they would shoot you or make you disappear,” he said.

Working as a draftsman on the day of the coup his office was lined with maps and schematics for future and current projects all around Valparaiso. All around town, soldiers were breaking down doors and barging into buildings. When they came across his office, they accused him of being a socialist sympathizer.

He would have his license revoked and his office robbed and destroyed. The junta held him as a political prisoner over suspicions of conspiracy against the government.

“I was detained with about 20 other people,” he said. “They stepped on my hands, they tried to break me psychologically and tried to intimidate me with gunshots to answer questions.”

They questioned him. They accused him and intimidated him for seven days straight, but they did not break him. He would later be released with all charges dropped against him.

At the time, the Chilean government was trying to stop any potential rebellion or insurgency within the country and suspected many on the left.

“I was more left-leaning in my political views, and I was friends with many people who considered themselves socialist or communist,” he said. “I saw a lot of people who I knew personally just disappear.

“I had my left-leaning ideas for sure but I was just a worker, not an activist.”

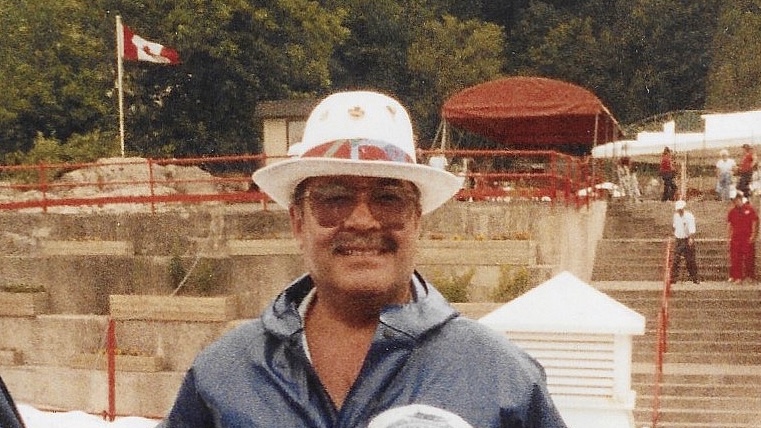

An old photo of my father, Pedro Riquelme, from 1987 during his first trip to Niagara Falls, Ontario. Photo credit: Alfonso Catalan

My father spent 12 years in Chile to care for and protect his family, but the government persecuted more people and threatened his life. He had to make a choice.

He decided to board one of the last two flights leaving Chile on Oct. 26, 1986, with one bag in hand and sought asylum in Canada.

“Everything I had stayed there and I had to start my new life here,” he said.

Starting a new life in Canada can be difficult for many immigrants, but my father’s inability to return to get his documentation from his home made it more difficult.

The Chilean government seized his documents and he could not try to go back.

“For the first 10 years, I wasn’t allowed to return to Chile,” he said. “I did not have my documents here to get permission to go, and my permanent resident status here was not approved yet.”

When he arrived in Toronto, he was taken to the Toronto Chilean Society, established to help other Chileans escaping persecution to settle in Toronto.

“When I arrived at Toronto Chilean Society, almost all of the people who came here were due to political persecution, some of them coming many years before me,” he said. “When the military hit occurred, many left for different countries, and a lot came to Canada because Canada was accepting Chilean refugees.”

There he met other Chileans with similar ideals, interests and stories, and one of the things some of them had in common was the love of their culture and folklore music. This love for folklore and shared experience helped them feel more at home.

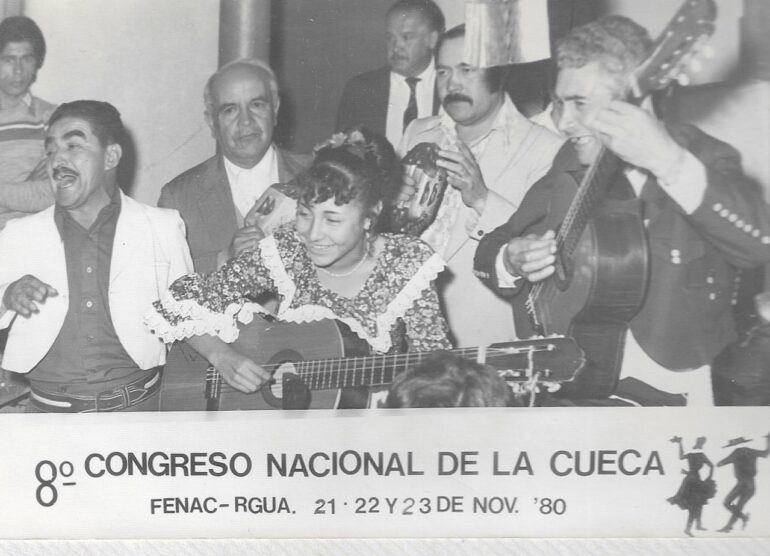

“I helped create the first Chilean folklore group here in Toronto, I taught classes for Cueca, which is the national dance of Chile, I assembled a group of artists called Las Guitarras Chilenas, and we still perform even today,” he said.

My father sang with the group for many years, keeping the culture and spirit of a free Chile they all remembered.

Pedro Riquelme (seen holding the tambourine in the middle right) is pictured with other performers at the 8th National Congress of Cueca in Chile. Photo credit: Courtesy

While a large part of the Chilean community in Canada returned to Chile once democracy was re-integrated in 1990, my father, like many other Chileans, stayed to live his new life here in Toronto.

“I still visit Chile when I can, but Canada became my new home and that’s why I chose to stay,” he said.

As another year goes by from the anniversary of ‘El Golpe del Estado de Chile’, thousands of Chileans in Canada and around the world are left to reflect on the events that relocated them and altered their lives forever.