By Scott McLaughlin, News Reporter

Shelley Atkinson has now spent more years as a widow than she did as a married woman.

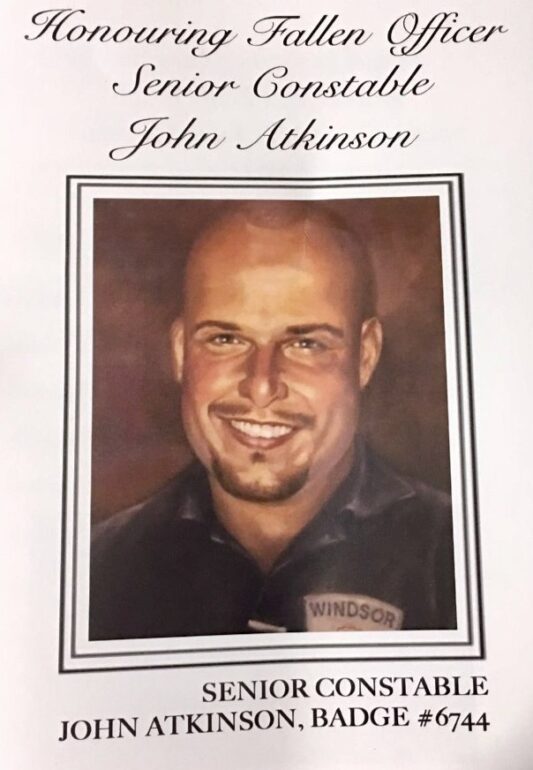

Her husband, Windsor Police Senior Constable John Atkinson, who was working undercover, approached two young men suspected of being involved in a drug deal outside a convenience store on May 5, 2006. He had noticed a bulge under one of their shirts that he suspected was drugs.

One of the suspects pulled out a handgun and shot Atkinson in the face, killing him instantly.

He was just 37 years old.

“He was so wonderful. I lost my best friend,” Atkinson said. “He was a good cop, but an even better husband.”

For her, his death is a reflection of the continuing rise in gun violence in Canada, something the federal government is now taking steps to curb that trend. Criminal use of firearms in Canada has increased by 42 per cent since 2013, according to Statistics Canada. In 2020, there were more than 8,000 incidents involving gun violence.

The federal government has recently tabled several bills regarding the sale of guns in response to this rise in gun violence.

The federal government introduced additional regulations to Bill C-71, An Act to Amend Certain Acts and Regulations about Firearms, on May 18. This bill expands background checks to applicants’ entire lifetimes and requires an application for Authorization to Transport.

“We are taking action to keep Canadians safe from gun violence,” said Marco Mendicino, Canada’s Minister of Public Safety. “To that end, we are bringing into force common-sense regulations that strengthen public safety through validated ownership, transparent business records keeping and license verification prior to purchasing a firearm.”

In addition to the amendments to Bill C-71, the Trudeau government also recently proposed multiple changes to Bill C-21.

Those changes took effect on Oct. 21, 2022, and placed a freeze on the sale and transfer of all handguns within Canada.

Since then, more measures have been proposed but not yet implemented, that would restrict ownership of certain shotguns, hunting rifles and even some antique cannons.

Existing gun laws in Canada also include the Criminal Law Amendment Act, which was put in place in 1977. The law banned many guns, including automatic weapons, as well as sawed-off shotguns and rifles.

Anyone who owns a gun must possess a Possession and Acquisition Licence (PAL).

However, not everyone thinks these steps are going to keep Canadians safe or get illegal firearms off the street.

Tony Sotera, owner of the gun store Guns N Ammo in Barrie, Ont., feels these new regulations were motivated more by political aspirations than by reducing gun violence.

“It’s a farce that the government is using to perpetrate legal gun owners,” Sotera said. “These crimes are not being committed by people who legally own and register guns.”

“Owning a gun is a privilege in Canada, not a right. And gun owners want to hold onto that privilege.”

Sotera said that ultimately these laws affect his bottom line more than doing anything to get guns out of the hands of criminals. His solution would be to stop guns from crossing the border.

In 2020, 70 per cent of all traceable guns used in Ontario gun crimes were originally from the United States, according to data from Ontario Police’s Firearms Analysis and Tracing Enforcement Program.

Sonja Plunkett, another SOLE member, has seen first-hand through her work with the group the pain that gun violence can bring. Her husband, Constable Robert Plunkett, was killed in while working undercover for York Regional Police in 2007.

“Obviously there’s a huge concern. Especially being in a police family you worry,” Plunkett said. “You worry what’s going to come of this.

“There needs to be stricter laws, there needs to be a better way to track where guns are, who has them, who should and shouldn’t have them,” she said.

“Whenever you hear the news of a police officer dying in the line of duty, you immediately think back to what happened to you,” Plunkett said. “My thoughts immediately go out to the friends, family and colleagues of that officer.

“It’s a very, very difficult journey,” she said.

Plunkett said there are many people who are responsible gun owners and use them for what they were meant for, including hunting.

“But there’s far too many guns in the hands of people who have no business having a gun, let alone an automatic weapon,” she said. “And it’s taking its toll on police officers, but it’s also taking its toll on communities in general.

“Something has to change,” Plunkett said. “I believe that starts with enforcement. There needs to be tighter restrictions on guns in general in Canada.

“We need to send a message that it’s not okay to engage in violence,” she said. “It’s not okay to kill other people.”

Former OPP officer Brenda Orr agrees Canada needs to stop the flow of guns coming across the border from the United States.

“A lot of these firearms that are killing police officers, as well as regular individuals, are illegal firearms,” Orr said. “I know it’s not the gun that kills people, but without the gun, they can’t shoot somebody.”

Orr, a founding member of Survivors of Law Enforcement (SOLE) and whose husband, OPP Constable Dave Mounsey, died when his cruiser crashed responding to a call in 2006, agrees that better background checks will make it more difficult for people with criminal backgrounds to obtain guns. However, she’d like to see even tougher gun laws.

Atkinson is also a member of the non-profit organization that started to support spouses and families of officers who died in the line of duty.

From 2019 to 2021, there were a total of six police officer deaths in Canada. But in just the past four months alone, five names were added to police memorials across Canada.

Four victims were in Ontario: South Simcoe Constables Devon Northrup and Morgan Russell during a domestic dispute; York Region Constable Travis Gillespie by a suspected impaired driver; and Constable Andrew Hong, in an unprovoked attack. All were shot to death.

The fifth was in B.C. when Burnaby RCMP Constable Shaelyn Yang. She died after being stabbed during a call to a transient camp.

Members of SOLE feel they have a unique perspective and a unique responsibility to speak out about gun violence in Canada.

More than 16 years after her husband died on duty, Atkinson continues to fight for stricter gun control in Canada.

“This is Canada. People have to realize we can’t just make this acceptable,” she said. “We can’t just turn the TV on and say, ‘Oh, it’s another death.’ Something has to change.”