Getting stuck in the snow can be deadly for Toronto’s wheelchair users, one disability advocate said.

“I’ve known people that have died being stuck in the snow. They got out of their taxi, taxi left, they didn’t make it to their front door,” Russell Winkelaar said.

Winkelaar is an actor and wheelchair user who lives in Toronto because the city is more accessible than his hometown of Peterborough, Ont.

Despite this, there are reasons to be concerned about the accessibility of city streets especially during the winter, he said.

“You know, if I went wheeling out at night and got stuck … it doesn’t take long to get cold,” Winkelaar said.

Though Toronto is often heralded as one of Canada’s most accessible cities, ice and snow still present problems for people using wheelchairs and other mobility devices.

According to the city’s Accessibility Design Guidelines, all accessible entrances, ramps, and steps should have snow and ice cleared as quickly as possible.

Main streets like Bathurst, Dundas and College Streets are usually pretty good, Winkelaar said.

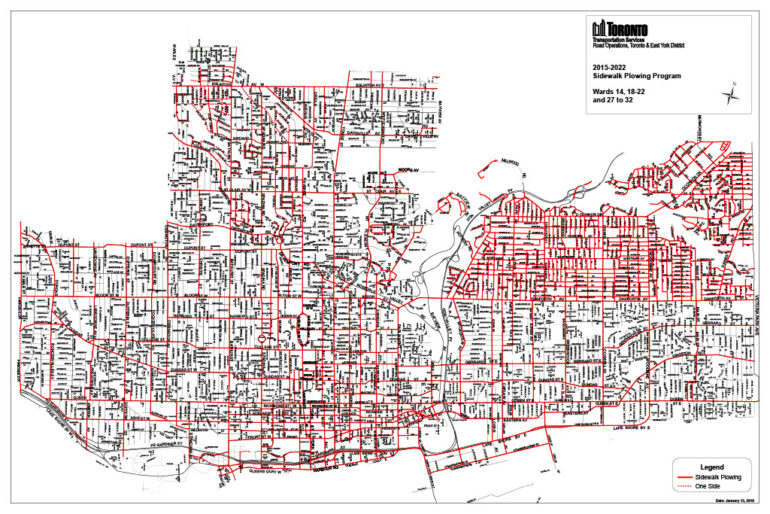

The city’s website states clearing ice and snow from most sidewalks is a municipal responsibility. But this can take up to 13 hours after a snowfall.

The problem, more often than not, is on smaller residential streets, Winkelaar said.

The city’s Snow and Ice Removal bylaw states home and business owners need to clear ice and snow within 12 hours. But often this just doesn’t get done, Winkelaar said.

“There’s always some spots that are bad,” he said. “Sometimes you have to go back half a block and cross the street and go the other way.”

The city does not enforce accessibility on sidewalks unless someone calls 311 with an issue — whether that be snow, ice, delivery trucks, sandwich boards or anything else that may block a sidewalk.

Tim Ross, a scientist with Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital and has a background in urban planning. His work focuses on institutionalized ableism, the idea that a mostly able-bodied society is ignorant of the needs of those with disabilities.

“It’s pretty difficult to be an able-bodied person and to have a comprehensive understanding of how these issues are experienced,” he said.

One solution to this problem is to include more people with disabilities in the conversations about how we build our cities, Ross said.

“People living with disability have a unique ‘positionality’ that gives them a unique and truly valuable perspective that we need to engage in our planning and design and service of communities,” he said.

Samantha Walsh, a social justice education PhD candidate at the University of Toronto-OISE, agreed.

“I’d like to see more marginalized people working together to inform city planning,” said Walsh, who is also a wheelchair user.

Assumptions made about people with disabilities is one of the biggest sources of unintended ableism, she said.

“The social imagination of disability informs policy in ways that I don’t think people think about,” Walsh said.

She regularly encounters people who assume someone with a disability can’t contribute meaningfully to society. These assumptions also inform city policymakers, she said.

Winkelaar suggests one way to combat these assumptions is to shift society’s thinking to a social model of disability.

Such a model recognizes the social and environmental barriers inflicted on someone with an impairment, rather than the medical model of emphasizing their physical limitations.

The Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (2005) protects people with disabilities from outright discrimination, but the government can’t mandate a change to society’s unconscious biases.

Luke Anderson, the founder of The StopGap Foundation, a company that provides ramps to businesses with stepped entryways, has used a power wheelchair since sustaining a spinal cord injury in 2002.

Education and awareness are the biggest tools in the accessibility fight, he said.

Able-bodied people need to have “conversations among their circles, around the dinner table, at home, in the office,” Anderson said.

He suggested getting involved in diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives within different community organizations.

People need to step up and amplify the voices of people who are often ignored, he said.

Winkelaar said it takes allies to push the cause forward.

“And we need more eyes and ears and hearts open to it to push it forward,” he said.