Sewon Hwang

People in the GTA woke up Jan. 12 to a loud buzz from their phones. The noise meant that something was wrong, an Amber alert perhaps, maybe a severe winter weather warning. The usual guesses were wrong and it wouldn’t be a usual day.

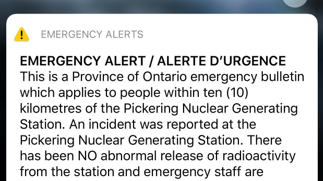

The alert warned of an issue at the Pickering nuclear plant, although there was no danger to the people who live within the 10 km radius to the plant.

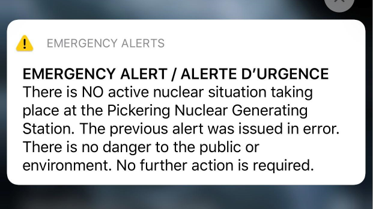

Cell phones buzzed again about an hour and a half later that morning, with a message that attempted to correct the first. This time, the alert read there was no active nuclear situation at the plant east of Toronto and that it was released in error.

It was a frightening notification to wake up to for Toronto resident Brandon See.

“It was scary, realizing that it was real,” he said.

The cause of the alarm is still unknown and remains under investigation.

Terry Flynn, a communications professor specializing in emergency communications at McMaster University, said miscommunication errors can hurt an organization’s credibility.

“When you’re doing a drill, all your partners are ready in the event that this information becomes public,” Flynn said. “They were caught unprepared and I think they’ve had to do some reputation management as a result of the mistakes.”

Flynn said the emergency alert system is relatively new, about three years old, and has not had enough time to test its efficacy. He said he believes the investigation into how the alert was released will reveal what went wrong, and how false alarms can be avoided.

In a 2017 news release from the Ontario Auditor General’s office, auditor general Bonnie Lysyk stated the province, the largest nuclear jurisdiction in North America, is not ready for a large-scale emergency.

“Plans have not been updated in years, and practising for emergencies through simulations are not frequently done,” she stated in the release.

The auditor general’s office, which refused to comment on the recent alert, released a 17-page report in 2019 as a follow up to the news release issued in 2017.

The report outlines a number of recommended changes proposed by the auditor general, but the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing implemented only 15 per cent of them while another 36 per cent were being worked on.

The report concluded the emergency management programme in Ontario had little to no progress on the changes the auditor general’s office had recommended.

The Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services plans to reference national and international best practices for performance measures related to emergency management as part of the internal review it intends to conduct and then implement a new process, although the exact plans were not available on the report.

See, however, is skeptical about the system and will remain so until the investigation concludes and adjustments are made.

“They should know their own system,” he said.