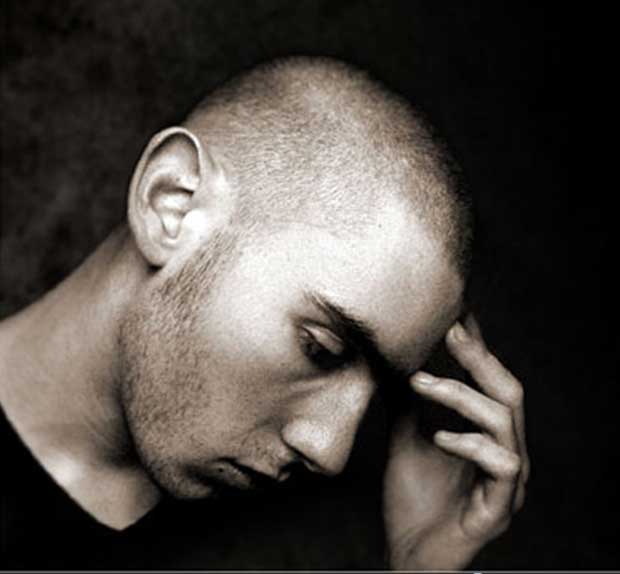

A new report reveals that 90 per cent of Canadians suffering serious mental illness are mostly unemployed due to stigma about their condition. Source: Andrew Mason; WikiCommons

by Rachel Landry

A report, titled Aspiring Workforce, has found that workplace-related stigmas surrounding mental illness may be costing the Canadian economy an estimated $50 billion a year in disability income and lost productivity.

The report reveals that 90 per cent of Canadians with serious mental illness remain unemployed largely due to prejudice about their conditions.

Jason Reid, author of Thriving in the Age of Chronic Illness, told Humber News it is extremely important that the stigma on mental illness be broken.

“There are going to be people absolutely crucial to the needs of various organizations (who are excluded),” he said. “They’re going to have special skills whether they are engineers or whether they have software skills.”

The report, conducted by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, the University of Toronto and Queen’s University, and commissioned by the Mental Health Commission of Canada, will officially be released on Wednesday.

Laura Templeton, a Toronto fundraiser, suffers clinical depression.

“I had to take a month off of work last year because I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning,” she told Humber News. “I felt like I had lead in my veins.”

She, who said she has experienced stigma over her condition, believes an employer’s accommodation of employees with mental illness plays a vital role in their success in the workforce.

“Sometimes I would be afraid to explain myself,” Templeton said. “If I have to call in sick because of my depression, I don’t know how to explain that because sometimes people don’t understand.”

The report’s release coincides with Mental Health Awareness Week, which began on Sunday and runs until Saturday. Awareness Week is an annual national public education campaign designed to help open the eyes of Canadians to the reality of mental illness.

“If we don’t look past the stigma of mental illness, we don’t allow those people into the workforce,” Reid said. “From an economic standpoint those companies aren’t going to thrive and grow in our economy.”

The report calls for early intervention on the issue and notes that the longer someone spends away from the workforce, the more difficult it is for them to get back to work.

Aspiring Workforce also urges governments to remove disincentives to returning to work, such as disability payments. Those receiving these payments often fear their financial situation could worsen if they leave those programs and return to work.

Researchers also found that working helps improve the lives of those with mental illness while reducing economic costs. For example, those who work use fewer health services than those who are unemployed.

The study argues that increasing employment of the mentally ill will dramatically reduce the $28.8 billion that is currently spent every year in public disability income for those with a mental illness.

Reid said that being in the workforce could help a person suffering with mental illness better cope.

“It gets them out of the headspace where, if you’re not working, you tend to spend a lot of time thinking about your illness and thinking about the reason why you aren’t working and people haven’t selected you for a job,” he said. “Getting into the workforce allows you to not be ruminating on those negative things all the time.”