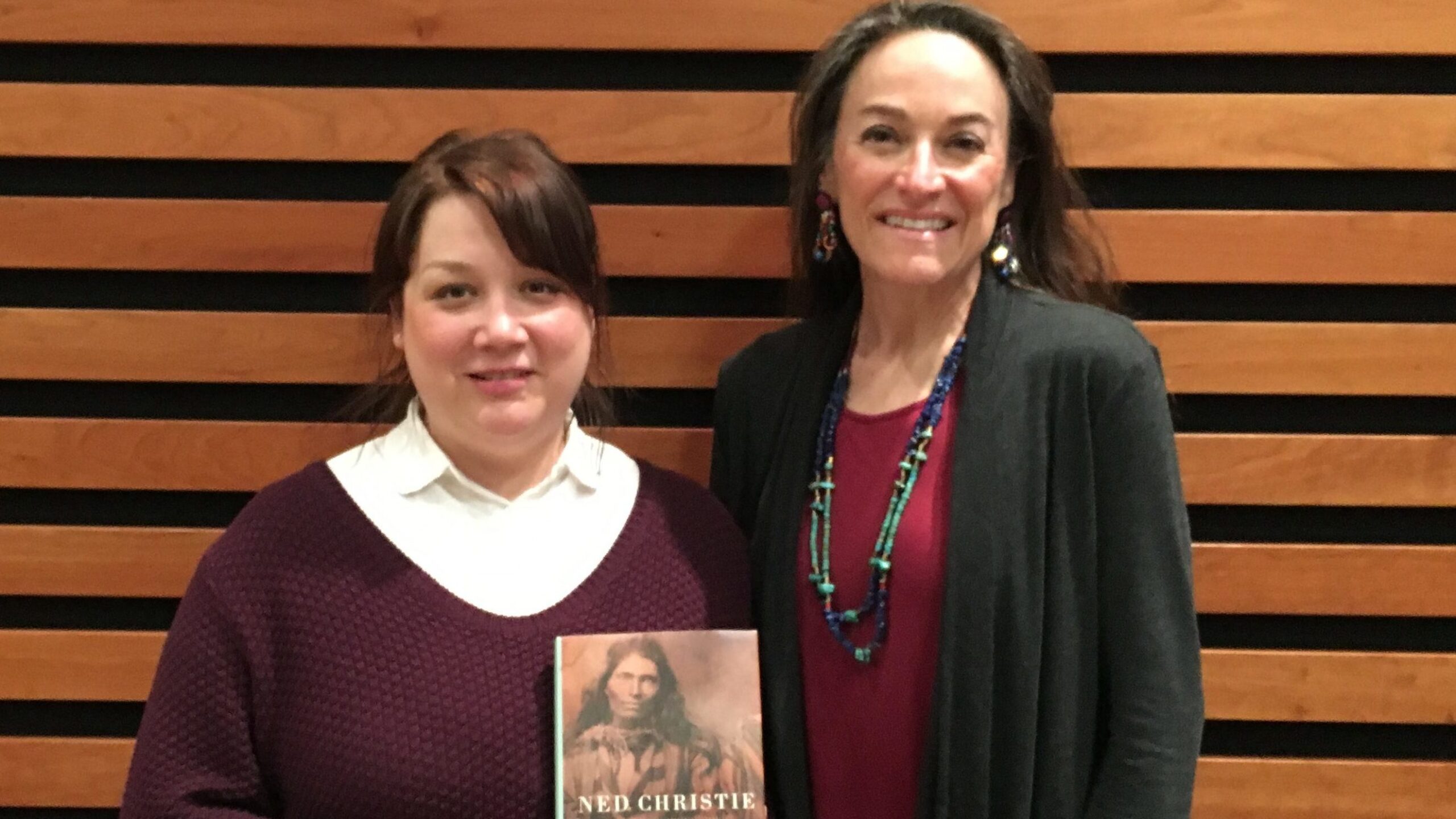

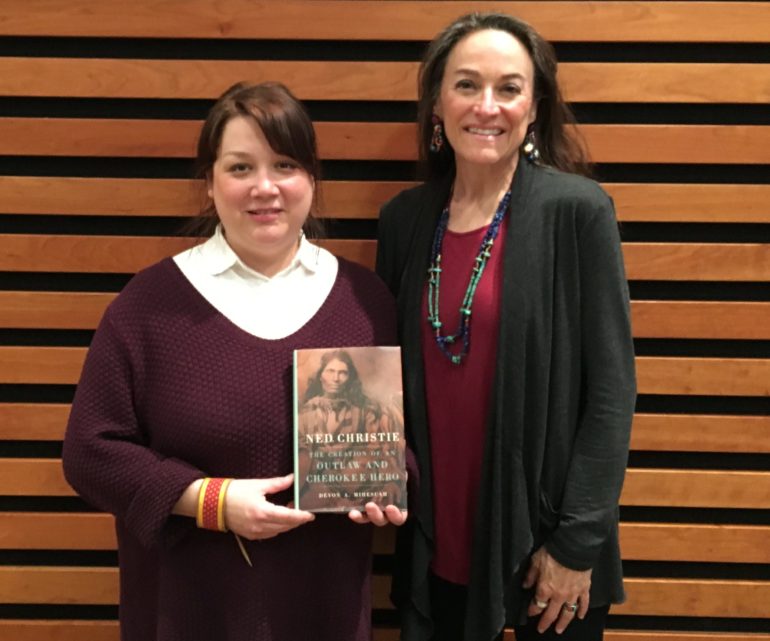

Falen Johnson (left), and Devon Abbott Mihesuah (right) posing beside Mihesuah’s book, “Ned Christie: The Creation of an Outlaw and Cherokee Hero” at the Toronto Public Library on March 22. (Michelle Guo)

Michelle Guo

“Slander or libel claims, no one’s was going to listen to you,” Devon Abbott Mihesuah said, in reference to how stories and facts had little room to be disputed in the 19th century.

Mihesuah was the special guest at a talk hosted by the Toronto Public Library about her book on Ned Christie, a Cherokee statesman, and the lies that were told about him.

Her book is titled “Ned Christie: The Creation of an Outlaw and Cherokee Hero”.

Mihesuah, an Indigenous history professor from the University of Kansas and member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, was joined in conversation by Falen Johnson, a Mohawk playwright and co-host of the CBC podcast, “The Secret Life of Canada.”

Minhesuah’s great great grandfather was an Indigenous U.S. Deputy Marshal and she saw Christie’s name being mentioned in various Cherokee historical files which initially sparked her interest.

“This was a man who was innocent yet there have been hundreds of stories that have made him out to be one of the most violent pathological killers in all of the wild west war,” Mihesuah said, in reference to Christie.

“I wanted to find out where came from and why did people do this? Why are they still writing about him in this fashion?” she had questioned.

Christie was a Keetoowah Cherokee traditionalist who had been appointed to the Cherokee national council in 1887.

“[Christie’s] family came over the Trail of Tears… so Ned grew up listening to stories about the U.S. government and the atrocities committed against not just the Cherokees, but also other tribes as well,” Mihesuah said.

His notoriety in wild west literature began after a U.S. Deputy Marshal named Daniel Maples came to the capital of the Cherokee Nation.

Maples decided to camp out next to a spring and left momentarily to go to a local shop but was ambushed and shot to death while returning to camp.

The murderer had hidden under the cover of darkness and escaped before being identified.

Six men who were known troublemakers in the Cherokee Nation area were later indicted at Fort Smith, Ark., for Maples’ murder.

The men blamed one another for the murder but all concluded Christie had been in the area.

Christie was then indicted but he refused to go to Fort Smith which resulted in a warrant being issued for his arrest.

He spent the next five years avoiding capture until he was eventually shot to death by a posse of men outside his cabin.

“There wasn’t a whole lot written about Ned until after he died in 1892 and I think it’s because people wanted to rationalize why it is these white marshals killed him,” Mihesuah said.

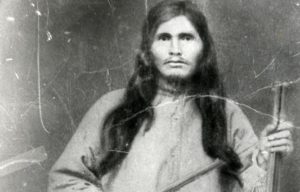

Ned is portrayed as around 6-feet-4 or 6-feet-5 inches tall in written accounts.

Ned Christie holding two guns. (flickr/Fort Smith National Park Service)

“I wanted to find out just exactly how big Ned was,” Mihesuah said.

She did this by comparing the weapons Christie held in pictures and discovered he was more likely between 5-feet-5 inches and 5-feet-7 inches tall.

Mihesuah had asked herself while researching the book why people felt compelled to make Christie so “big and huge and just capable.”

“I think it’s because the bigger and ‘badder’ the bad guy, this makes the people who took him down look even bigger and ‘badder,’” she said.

“It wasn’t just the height that was exaggerated with Ned, it was his ability to shoot a weapon… they exaggerated the type of house he lived in [as well],” she said.

It was reported Christie had constructed a large fort for his residence which had a view from all directions and the ability to shoot anyone within a mile’s distance, Mihesuah said.

“In reality, he had a little cabin,” she said.

There was also a story about Christie tarring and feathering a shopkeeper.

“There is something about this masculinity issue during this time period and people take a very very great interest in this and it’s not necessarily the women who like it, it’s really the white males,” Mihesuah said.

Mihesuah draws on the historical rise of boxing and football as becoming part of the masculine norm during this time period.

“People want to see these kinds of stories,” she said. “Ned fits perfectly into those narratives.”

“It’s so interesting … because we have social media now, it’s just so surprising to see someone not in control of their identity at that time and that was really the case,” Johnson said. The book sheds light on newspaper practices of the era, that “if you wanted your paper to sell or your article to do well … it’s almost like fake news,” she said.

Mihesuah said Native people during the 19th Century had no recourse in dealing with the reporting.

“Ned really did serve a purpose and his story still serves a purpose,” she said. “Ned’s story is a comforting story for people who need to know that good will triumph over evil and Ned just happens to portray the bad guy in this story.”

“Some lawmen walked into newspapers directly and told the reporters their story so they were contributors to their own anthologies,” Mihesuah said. “They could do anything, you would think we were watching Avengers: Infinity War or something.”

An audience member asked if Mihesuah thought Christie was a hero.

“Not necessarily, but Cherokees would,” she said.

Mihesuah said Cherokees argue Christie was constantly speaking against the railroads’ intrusion into Native life.

“I didn’t see any evidence that he really did that,” she said. “There was nothing in the house or senate documents where Ned got up and talk for hours about these white intruders or against the railroads.”

“Occasionally he would say something,” Mihesuah said. “Many Cherokees like to argue because he was so gung-ho about this, this is why he was killed.”

“That take is thin for me,” she said. “I think he could be seen as a hero in that he didn’t go out and try to retaliate because they were trying to kill him.”

It took a long time to decide to write this book, Mihesuah said.

“The Christie family today is quite big,” she said. “Out of respect for the Christie family, I really felt like I needed permission from them to get their ok before I dove into this.”

Johnson asked what the process of getting permission entailed.

“I will write this book and I will let you look at it before I submit it,” Mihesuah said.

“Well, it really is because another person had written a book about Ned Christie and she gave the book to the family to look at and they did not approve and they pointed out errors specifically … and she published it anyway,” Mihesuah said.

“And I thought no, you just don’t do that,” she said.