Toronto Police dig at a property Bruce McArthur previously worked on. (Canadian Press)

Kit Kolbegger

Crown attorney Craig Harper and defence lawyer James Miglin presented arguments in court Tuesday on how confessed serial killer Bruce McArthur should be sentenced.

McArthur pleaded guilty to eight counts of first degree murder last week. He found his victims in the Church-Wellesley area of Toronto, commonly known as the Gay Village.

McArthur was a landscaper, and used his trade to cover his crimes. His victims’ bodies were found dismembered in planters at a property he often worked at, and in the ravine behind the house.

The minimum sentence is life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years. Harper argued that a longer period of parole ineligibility is necessary to fit the “enormity” of McArthur’s crimes.

“This case has a haunting quality to it,” Harper said.

Justice John McMahon will decide Friday between concurrent or consecutive sentences. In a concurrent sentence, time is served for multiple crimes at once. In a consecutive sentence, time is served for each crime back-to-back, meaning longer jail time.

Parole ineligibility can also be served consecutively or concurrently. Only six of McArthur’s murder convictions can have consecutive terms of parole ineligibility, as the law allowing it was only introduced in 2011.

Harper argued that McArthur should serve two consecutive terms of parole ineligibility, or 50 years. McArthur would be 116 when he could apply for parole.

Defence lawyer James Miglin said McArthur’s age was a factor the judge should consider in sentencing McArthur.

Both lawyers drew comparisons to Elizabeth Wettlaufer, the former nurse who killed eight patients in a care facility. She received a life sentence and will be eligible for parole in 25 years.

Harper said Wettlaufer was only caught because she came forward about her crimes.

“But for her confession, she would have gone to her grave without anyone being the wiser,” he said.

Miglin pointed out that Wettlaufer is only 50 years old. When she is eligible for parole, she will be 75. McArthur would be 91. According to Statistics Canada, the average Canadian lives 79 years.

He said all prisoners should have some hope, “no matter how faint,” that their imprisonment will end.

McMahon called McArthur’s crimes heinous, saying, “Innocent folks were lured to their deaths on the premise of consensual sex.”

He also said McArthur’s guilty plea had not only kept the court from wasting time and resources, as the defence suggested, but that the plea had saved the victims’ families from a drawn-out and brutal trial.

“When you have eight murders, to me, that’s a big factor,” he said.

McMahon will consider statements from the family and friends of McArthur’s victims when he passes sentence.

Over thirty statements were provided to the judge. There wasn’t enough time to read them all at the hearing on Monday, so the last statements were read before the Crown and defence made their arguments about sentencing.

The impact statements provided a deeper look at the eight victims’ lives.

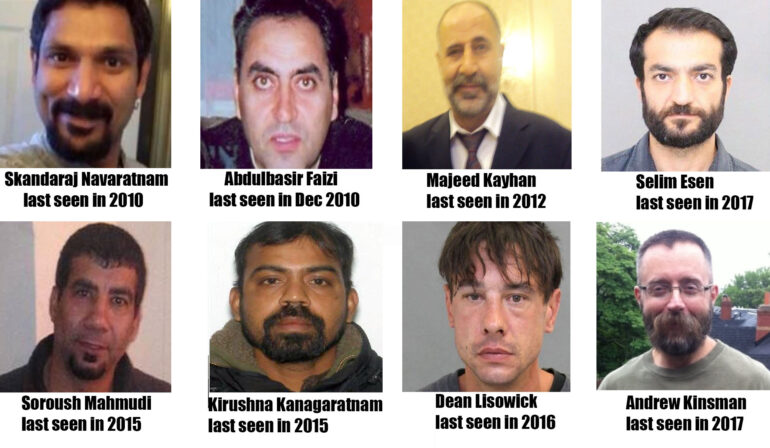

The collage of all McArthur’s victims. (Kateryna Horina)

Skandaraj Navaratnam, 40, killed in 2010

Skandaraj Navaratnam, or “Skanda”, was a Sri Lankan refugee. Jean-Guy Cloutier said Skandaraj was like a brother to him. “He would text me every day just to say have a ‘good day,’” he wrote. He described Skandaraj as spiritual, a man who had made a place outside to meditate. He loved nature and animals, especially his pet husky.

Skandaraj’s friend Phil Werren said he was a highly-educated man “unbeatable at Scrabble.” Werren said he learned a lot from Skandaraj, and that even their arguments were valuable to him.

He was the “livewire” of their family, according to his brother, Navaseelam Navaratnam. Navaseelam wrote in his victim impact statement that his brother was their mother’s favourite son. The family has hidden Skandaraj’s death from her, because of her poor health. She looks forward to meeting him face-to-face again someday.

Abdulbasir Faizi, 44, killed in 2010

Kareema Faizi, Abdulbasir’s wife, wrote a statement read by the Crown, described how hard it was to get by without her husband. She works 16 to 18 hours a day now, trying to provide for their family.

“My daughters suffer terribly,” she wrote. “They pretend to be strong in front of me. But when they are alone in their room, they take a picture of their father with them. I hear them crying constantly.”

Kareema’s daughters were six and eight at the time of their father’s disappearance. Kareema was the only one to submit a victim impact statement for Abdulbasir. He had reportedly hidden his sexuality from his family.

Majeed Kayhan, 58, killed in 2012

Majeed Kayhan left behind older siblings, nieces, nephews, two children and three grandchildren, his brother Jaylil Kayhan wrote in a victim impact statement that was read by the Crown.

“I know that this letter is supposed to focus on how this has affected me,” he wrote, “but I belong to a family and it has affected all of us in tremendous and different ways.”

Majeed’s son reported him missing about a week after he was killed. Majeed kept pet birds, who were dead by the time his apartment was entered.

Jaylil’s was the only victim impact statement given.

Soroush Mahmudi, 50, killed in 2015

Umme Fareena Mazook, Mahmudi’s wife, openly wept in court as the Crown read her statement. They were married in 2003, and she described Mahmudi as her soulmate. They were both Sri Lankan.

Mahmudi left work early one day and then texted her that he was going out with some coworkers. He never came home, and that was when Mazook knew something was wrong.

“He always came home,” she wrote. She said that when she heard the news that her husband had been murdered, she fainted.

“I will always be reminded of how my beloved and innocent husband was brutally murdered,” she wrote.

Mazook was the only person to give a victim impact statement for Mahmudi.

Kirushna Kanagaratnam, 37, killed in 2015

Piranavan Thangavel arrived with Kanagaratnam on the MV Sun Sea in 2010, when they came to Canada by boat as refugees. There were 492 Sri Lankan Tamils aboard.

“The day that we reached the shores of Canada, as refugees, was the day we found courage and hope in our hearts,” Thangavel said.

Thangavel said that as refugees they faced uncertainty and fear in Canada. That fear had only been heightened by Kanagaratnam’s death.

The MV Sun Sea incident was denounced by Amnesty International, which wrote in 2011 that the government was investing more time investigating the Sri Lankans’ refugee claims than it did in other cases.

Kanagaratnam’s refugee claim was denied. The Crown said it was likely he wasn’t reported missing by his friends since they could have just assumed he was hiding from deportation.

Thangavel said he and his friends had witnessed violence and torture in Sri Lanka.

“For us now to hear of such a horrible death,” he said, “we who live in this world as refugees feel like there is no safety anywhere in the world.”

Kirushnaveny Yasotharan, Kanagaratnam’s sister, wrote in her impact statement, “I don’t want to live in this world which is so terribly cruel.”

Dean Lisowick, 47, killed in 2016

Gerry Montanti, Lisowick’s uncle, described him as a creative person who sent his mother paintings and carefully chosen cards for special occasions.

“He was very proud when his daughter Emily was born,” Montanti said. “Shortly after that, however, his illness took control of him and he disappeared into the streets of Toronto.”

Emily Bourgeois, Lisowick’s daughter, wrote a victim impact statement read by Cantlon. She said when she went to Toronto in her teens, she often wondered if she might pass by him and not even know it. She thought of him often.

“I even thought maybe he turned his life around and found work and nice lady and lived in a big house with kids of his own,” she wrote. “Now I know that the worst I thought was actually true.”

Bourgeois has one child and another on the way. She wrote that she knows they will ask her about their grandfather some day.

“I’ll have to tell them what happened and how he got taken away from the world and never got a chance to right his wrongs or better his life,” she wrote, “and that’s not going to be an easy conversation for me.”

Julie Pearo, Lisowick’s cousin, said that she missed him dearly. She said she couldn’t hate McArthur.

“I’ve never spoken his name,” she said. “I’ll never speak his name. At first, it was deliberate to render him insignificant. It worked. Now he is like the waiter at lunch. He is the guy who killed my cousin.”

“I cannot hate him. I’m not even angry with him. Other people want me to be, but I’m just not.”

Pearo said her heart and head were too full memories of Lisowick — “movie reels” of the two of them laughing — to have room to hate McArthur.

Selim Esen, 44, killed in 2017

Richard Kikot, a friend of Esen, described him as a “romantic” who had struggled with substance abuse and who didn’t always have a place to stay. Esen told Kikot that when he didn’t have anywhere to go, he would walk the streets of Toronto, believing he would eventually cross paths with “the one.”

“Where do you go when there is nowhere to go? Who do you turn to when there is nobody there?” Kikot asked. “This was present in my mind when Selim’s remains were identified.”

Gab Laurence, from St. Stephen’s Community House, said Esen had just completed their Peer Support Training when he was murdered. Esen was going to begin his work accompanying people to their appointments, facilitating workshops and running groups in housing sites.

“Selim was at a turning point in his life,” Laurence said, going on to describe Esen as compassionate, caring, and inquisitive.

Nadia Wali read a statement from Esen’s family, who live in the UK.

“We can’t come to terms with his savage murder,” she said. “It is like part of our body is cut into pieces and will be bleeding forever.”

Andrew Kinsman, 49, killed in 2017

Meaghan Marian, Andrew’s neighbour, said he was a warm person, if curmudgeonly at times. She called him a “fabulous, but clumsy” cook, who she could hear through the floor between them, cursing dropped plates.

He was sweet, she said, looking after her pet birds when she went on long research trips to China.

“He taught them to eat green vegetables as treats,” she said, “and he read aloud to them daily, explaining that he knew birds needed a lot of social interaction but he wasn’t quite sure what they liked to talk about.”

Greg Dunn said Andrew was like a brother to him, and the two of them often went camping and hiking.

“You have to learn to live with the ‘what ifs,’” Dunn said. “What if I had taken him camping the day he died? What if we had gone for a hike?”

Stephen Kinsman, Andrew’s brother, said he had started drinking after his brother’s difference, to help him sleep and keep him from wondering if Andrew was alive. He said he has begun to suffer from nightmares.

“I look at strangers differently now,” he said, “wondering if they are capable of such acts.”