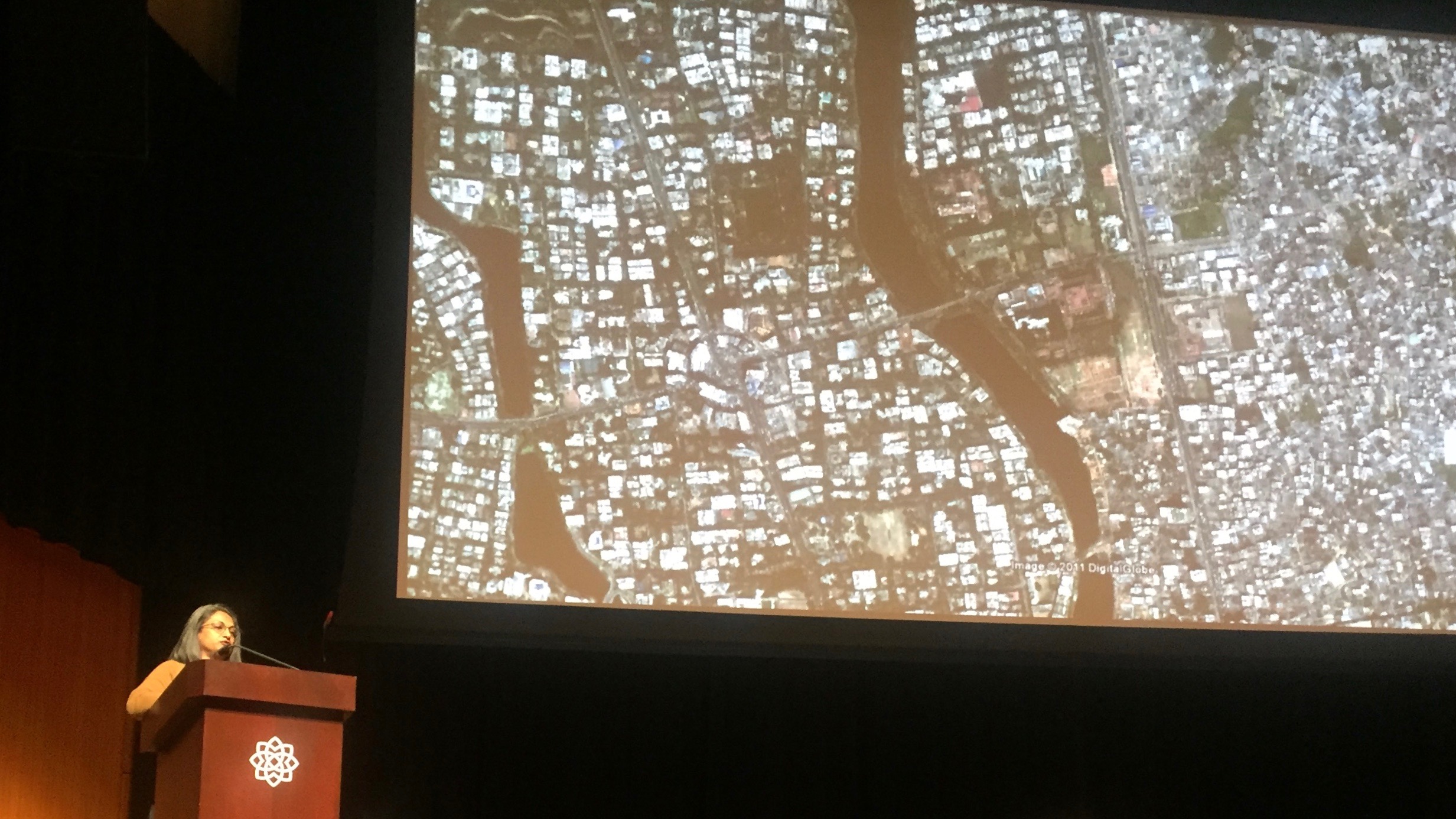

Marina Tabassum speaking on stage at the Aga Khan Museum with an aerial map of Dhaka, Bangladesh, on the screne on Jan. 19 . (Devin Linh Nam)

Devin Linh Nam

Award-winning architect Marina Tabassum’s architecture helped capture her nation’s history, by intertwining the past, present, and future in her designs.

When Tabassum was 27 years old in 1998, she helped lead the winning bid to build the Independence Monument of Bangladesh and the Museum of Independence.

“That was a big commission,” Tabassum said Jan. 19 at the DesignTO Festival, which showcases design projects that are making a difference in communities locally and globally.

“A big responsibility to design a monument which is to the independence of your country,” she said.

The monument tower, completed in 2013, inhabits an ample green space with the museum located underground, which reflects on the struggles Bangladesh endured to achieve independence.

“Memory and sadness always urge the subterranean,” said Tabassum, who was hosted in part by the Aga Khan Museum.

“That is why it is inside the earth. Whereas the celebration part, which is above, represents the future of a nation,” she said. Thousands of Bangladeshi people now come to the monument annually on Dec. 16 to celebrate the birth of a nation.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BngedvEAxQT/

The DesignTO Festival kicked off Jan. 18 with exhibitions, installations and events popping up all over Toronto. It runs until Jan. 27.

She is the principal architect and founder of Marina Tabassum Architects, as well as the academic director of the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements, and previously held a teaching post at Harvard Graduate School of Design.

The city where Tabassum was born – Dhaka, Bangladesh – is the site where most of her architecture lives, including the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque.

The Bait Ur Rouf Mosque, completed in 2012, won her the 2016 Aga Khan Award for Architecture and Jameel 5 Prize.

It serves as a place of worship but also as a place to congregate and enjoy, and because of Bangladesh’s climate, the mosque is porous to allow light and air to flow freely throughout acting as a natural air conditioning system.

“Architecture for me is a manifestation, or let’s say a response, of place,” Tabassum said.

She honours place by thinking about the Bangladeshi landscape, the materials available and the needs of the Bangladeshi people.

Dhaka, Bangladesh, skyline showcasing the city’s density. Source: Pixabay

The Asian country has a moderate climate with an extremely wet monsoon season and an extremely dense population. Tabassum’s architecture tries to solve problems that arise from an impermanent landscape and a lack of space.

“The challenges when trying to build in that climate, landscape, density, and poverty, and trying to deal with everything that is local, it was really impressive,” said Donna Lamb, who attended the talk out of interest with her husband, David.

What impressed audience members the most was Tabassum’s work in rural areas in Bangladesh, which centred around community building, education and reclaiming tradition.

“The one thing that stood out was the community design and communal design process she implemented in rural areas,” said Matthew Kelling, an urban planner with Urban Strategies in Toronto.

“It didn’t feel like false incorporation because sometimes you sell those things,” said Katarzyna Dominiak, a Polish architecture student visiting Canada for the first time.

“But here it actually seemed authentic,” Dominiak said.

Tabassum’s design philosophy regarding handcraftsmanship and porosity can seem impossible to implement in Canada’s extreme climate and cultural environment, but it is her commitment to her people and community that is transferable anywhere.