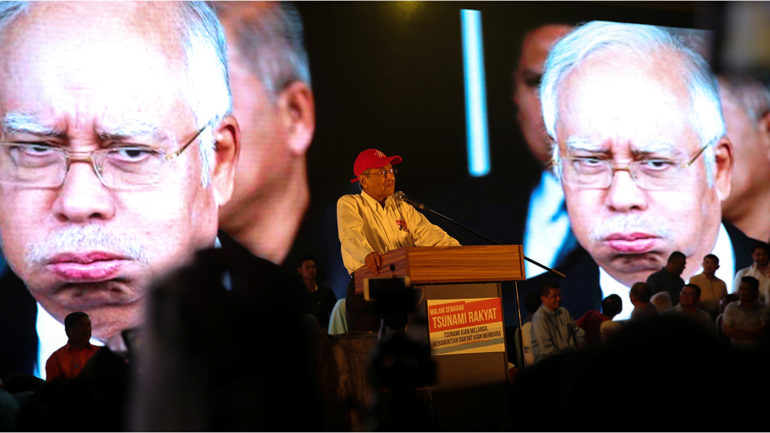

Former Malaysian Prime Minister and candidate for opposition Alliance Of Hope, Mahathir Mohamad speaks, as screens show pictures of Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak, during an election campaign rally in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, May 6, 2018. (REUTERS/Athit Perawongmetha)

Noman Sattar

A number of controversial policies led to the ouster earlier this month of the ruling party in Malaysia after 60 years, a senior journalist in that country told Humber News.

Malaysian politics took a historic turn on May 10 when Mahathir Mohamad, 92, took the oath as that country’s 7th prime minister.

His party’s win was a shocking election result.

“The result were unexpected, the opposition knew there is an anger among people, but they did not know the degree of anger,” Jahabar Sadiq, Editor at Malaysian Insight told Humber News.

Most people “did not know that former prime minister, Najib Razzak and his party would have been wiped out,” said Sadiq, whose website is widely read in the region.

On May, 9, Malaysian voters decisively rejected the seven-year rule of Najib and the 60-year continuous rule of the Berisan National Coalition.

It was the first defeat of the ruling party since the independence of Malaysia in 1957.

FILE PHOTO – A combination photo of Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak and former Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad (R) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Jan. 25, 2016 and Mar. 30, 2017 (R). (REUTERS/Olivia Harris REUTERS/Lai Seng Sin(R)/File Photos)

Malaysia’s economy seemed to be designed to benefit corrupt, elite politicians, cronies and business leaders who ran-up large debts and landed the country in a financial crises, Sadiq said.

A new goods and services tax was a particular flash point, he said.

“People were angry,” he said.

“They think this prime minister is enjoying himself while having people’s money,” he said.

On Wednesday Mahathir’s new government announced it would reduce the GST to zero as of June 1, effectively abolishing it. The move is expected to spur spending in the Southeast Asian nation.

Another irritant for many people came in April when Malaysia became the first country to legislate on fake news.

The Malaysian Anti-fake News Act laid out penalties of up to six years in prison for publishing false news, reports, data, and information. The law did not address what qualifies as fake news, fueling fears it will be used against the freedom of press.

Najib took the blame for the bill’s unpopularity, Sadiq said.

“He was so unpopular, he was bringing up laws to restrict news that called ‘fake news law,’ he was deregistering parties, so there is a combination of factors that basically made people angry,” Sadiq said.

In contrast to that kind of foreign support, Mahathir’s pro Muslim policies made him popular at home among Malaysians and helped get him elected.

Sadiq said he expects a change in tone from the new government.

“I think Mahathir will be closer towards third-world countries and the Muslim countries, and he will keep distance from the Western world,” Sadiq said.

Politician Anwar Ibrahim shakes hands with Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad at National Palace in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia May 16, 2018. (Department of Information/Krish Balakrishnan/Handout via REUTERS)

Right now, Sadiq said Mahathir is being seen positively because of his work to develop Malaysia, including building a system of ‘crony capitalism’ that has helped poorer segments of society.

Another positive sign is the release on a royal pardon Wednesday of Anwar Ibrahim, Mahathir’s favored successor and an opposition leader in Najib’s government. Ibrahim aims to turn Malaysia into a new high tech business hub like Singapore.

“People’s expectation from Mahathir is to set the country right, to reduce the taxes, to make sure they get rich again,” Sadiq said.